I currently have a lack of both time and money, which makes it difficult for me to attend more than my local practice for fencing. What I do have is a lot of time for reading while on the train. So, similarly to what I did when I decided to learn more about bread making I picked up some books.

The first one had very little to do with rapier: Warrior to Soldier, 449-1660. It’s a history of warfare in England from the Saxons right through to the New Model Army. It’s a great overview for anyone in the SCA with an English persona. It helped me to understand the rapiers position in England, as that of a day to day sidearm. I knew that it wasn’t a military weapon, but to see the evolution of the military sword and armour was very enlightening. Though the rapier came to prominence in England, the decrease in armour was actually because of the firearm. I always figured that firearms in general brought about the change in armour, but it wasn’t actually until the advent of the musket (which at the time was so heavy it needed a prop) that armour became useless. The first muskets allowed a half trained man to kill someone in the heaviest armour who had been trained from childhood. Although new armour was designed that could withstand a musket shot, it was so heavy that it required a man to be on horseback, and slow. It was useless on the ground, and couldn’t be used to protect the horse as it was too heavy. So if the cavalry had the bulletproof breast plates on their horses were still vulnerable, and the musketeers just aimed for the horses instead. The armour was so heavy that people refused to wear it. They would rather wear little armour and be fast.

The book I”m currently reading is Methods and Practice of Elizabethan Swordplay. It’s an older book, and is aimed at theatrical fight directors who want to be more authentic. It’s focus is the history of rapier fighting, and how it evolved in England. They focus on the three english manuals, Di Grassi, Saviolo, and Silver. Two rapier manuals and one response to it. It’s great to see a look into the psychology of the time. I find that too often SCA rapier fighters forget that this was a weapon designed to kill in a private brawl. It’s especially interesting to see that most English duels before the rapier ended up with one party injured, but not mortally. The rapier changed that. It brought a new level of dangerousness to the duel.

The rapier came into vogue with its lightness, its quickness, its deadliness, and oddly enough, because the celebrities of the day were using it. The people teaching the rapier tended to be minor nobility, which made it easier for the other nobility to learn from them, as they would prefer not to have a fencing master who was of a significantly lower class. It’s an odd way for the rapier to come into England, but it does explain why it took far longer for the rapier to enter England than anywhere else, what with the amount of push back from the teachers of “English Fencing”.

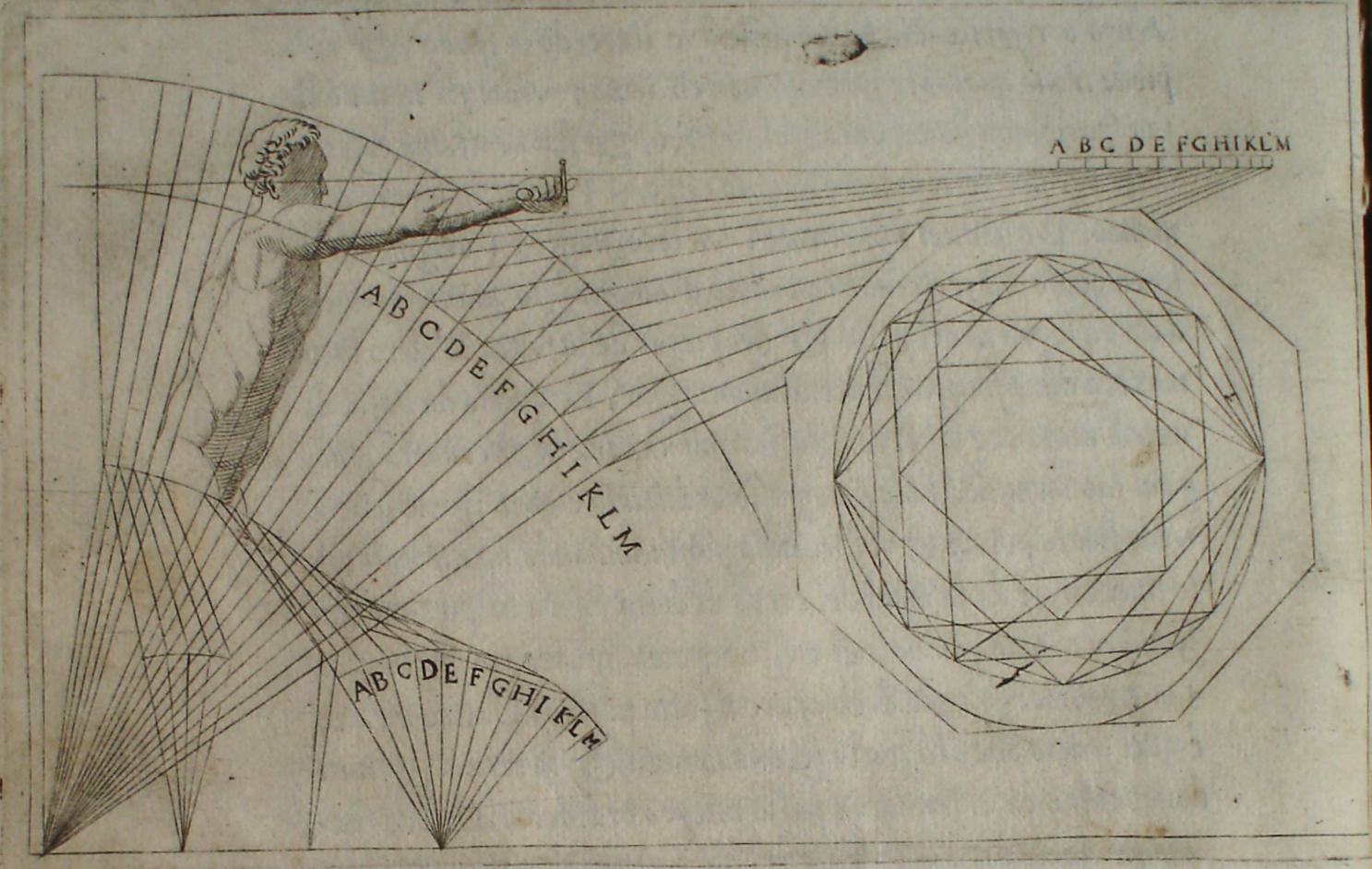

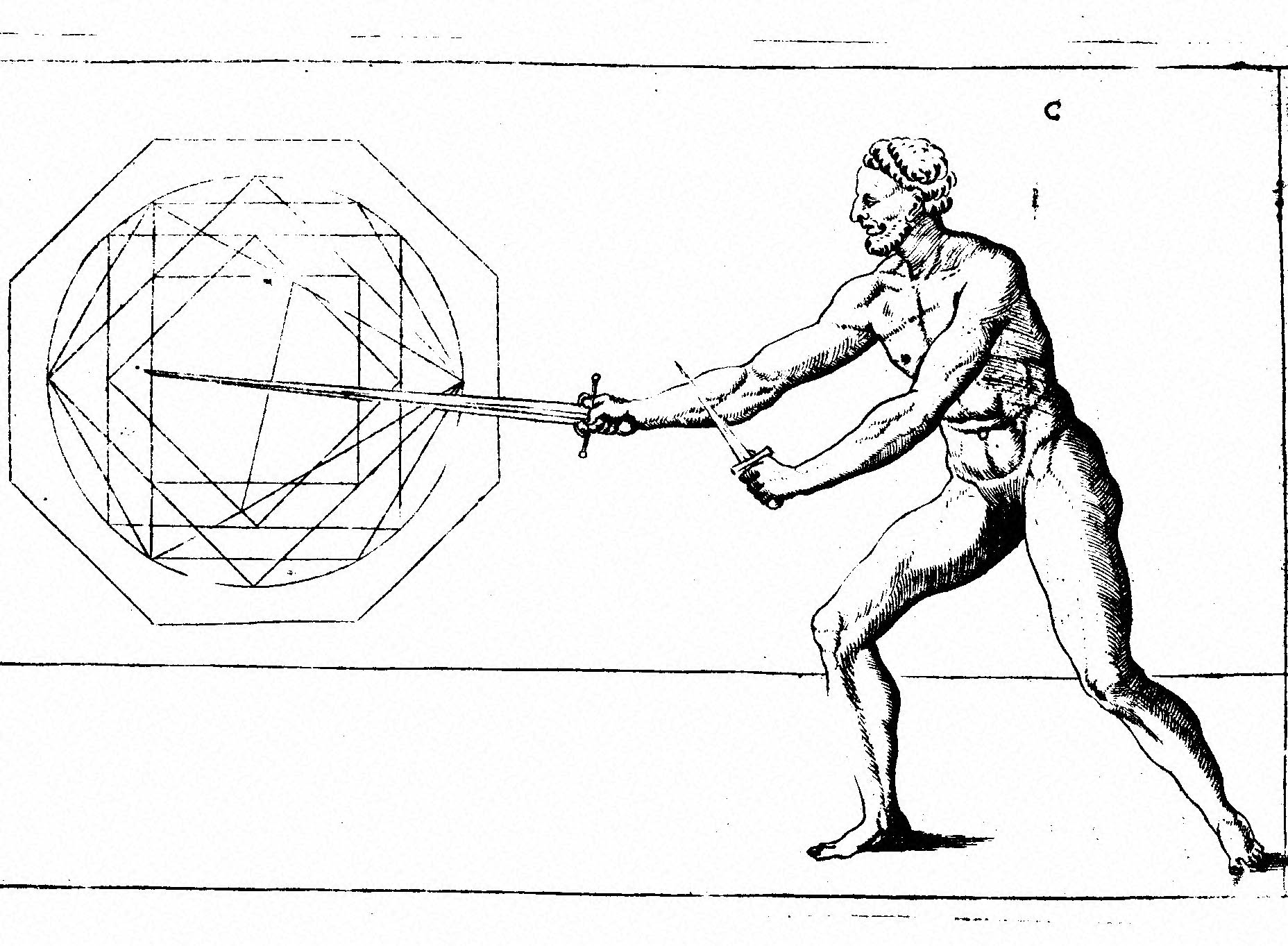

So far I’ve only gotten far enough through the book to have finished the section on DiGrassi’s combat. The three guards seem interesting to me, the high ward seems a fairly standard prima, nothing spectacular in this. DiGrassi seems to list the same advantages and disadvantages as everyone else. The broad ward has always confused me. I find that it is greatly lacking in defense. The odd thing is that although the description and the pictures (both in English and Italian manuals) have the guard placed at least a foot and a half from the body with the blade facing in all of the attacks he recommends from this ward could be just as easily done from our standard tertia. In fact he moves from his broad ward into modernly recognizable parries. I suspect that the broad ward is more a way of opening up a specific target so that you know exactly where your opponent will be striking you.

Which leads me to the low ward. I know that I dismissed it as being primarily good against cuts, and it left too much of the upper body undefended, and was too counterpunchy, but now I think that it may have its place. It seems to be a good choice to use in conjunction with a dagger or shield. The biggest advantage I see in it is that it allows you to keep your opponent from gaining your sword early without sacrificing speed or putting your point into a location where it is not threatening. I think that it may be a very functional ward if used correctly, similar to the demi-refuse that I was using before Christmas. I think I may try using the low ward in practice this week and see how it fares. There must be a reason why it was so popular in the late 16th century.

Something that I like about DiGrassi is that it doesn’t rely on leaning forward or back as part of your defence, and seems to prefer a balanced stance over a few inches one way or the other.

The next section in the book is about Saviolo, so I will likely have more thoughts about that later. After the current book my plan is to read one on the basics of clasical fencing. It’s called The Science of Fencing and it seems to have some great thoughts on timing, tempo, measure, and body mechanics. My goal is that even if I can’t be fencing all the time I can be learning about it. Way to put my A&S part of my brain to work on rapier.

0 Comments